Eating out for Jackson Esteves, 10, from Bayville, Long Island, had always been a gamble for him and his parents. With severe food allergies of various kinds—peanuts, dairy, sesame seeds, to name a few—having a meal in a restaurant, or even at a friend’s house, came with challenges and stress.

When Jackson’s parents were told that it could be possible to address at least his peanut allergy and make it less severe, they were ecstatic. “When the opportunity to participate in this trial was presented to us, we jumped,” says Holly Esteves, Jackson’s mother.

Jackson was enrolled into a study, named CAFETERIA, which explored whether it is possible for people who are allergic to peanuts—but are able to take small amounts—to be desensitized to the allergen through a form of immunotherapy that gradually exposes the individuals to peanut butter.

The study, funded by the National Institutes of Health’s National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, found that participants who received allergist-supervised treatment with peanut butter were able to tolerate more peanut butter than before, without any allergic reactions.

The findings, published in NEJM Evidence, suggest multiple ways forward for the research team.

“There are still many things we need to know to really broaden the impact of this research,” says Scott Sicherer, MD, Director of the Elliot and Roslyn Jaffe Food Allergy Institute at Mount Sinai Kravis Children’s Hospital.

“Can we apply this to other allergens? How do we know what the right threshold of tolerance should be? How do we identify whether patients are right for this kind of treatment? The road ahead is an exciting one,” says Dr. Sicherer, who is also Chief of the Serena and John Liew Division of Pediatric Allergy and Immunology in Mount Sinai’s Department of Pediatrics.

Read below to learn more about how the CAFETERIA study helped Jackson live a fuller life, the next steps for researchers, and what it takes to get there.

A Constant State of Hypervigilance

The Esteves family on vacation, from left to right: Craig, Violet, Holly, Jackson, and Sailor Esteves.

Jackson had lived with an allergy diagnosis pretty much since birth.

“It is a constant in our lives. I live with a seriousness that I used to be able to escape, but eventually, being in a perpetual state of high alert takes its toll,” says Ms. Esteves. Every day, several times a day, she worries that her son will encounter an allergic reaction. “I often feel worn down and tired from the worry, but I remember to slow down, breathe, and find gratitude in the little things.”

Over time, the Esteves family learned to adjust to a “never normal.” “It’s not necessarily easier, it is just what we’re accustomed to,” says Ms. Esteves.

That means that when Jackson goes to school and camp, he carries his own lunch and safe snacks. Going to a friend’s birthday party? He has to bring his own meal and cupcake.

“When we travel, we also need a kitchen accommodation to prepare food,” says Ms. Esteves. “I’ve learned how to order in restaurants, how to engage in constructive conversations with school and camp staff, and really how to advocate for my son always.”

The CAFETERIA study kicked off in August 2019, and Jackson was one of 73 participants in the trial. Participants were randomly and equally assigned to either the ingestion group—starting with one-eighth of a teaspoon of peanut butter, and eventually increasing to one tablespoon—or avoiding peanut products entirely.

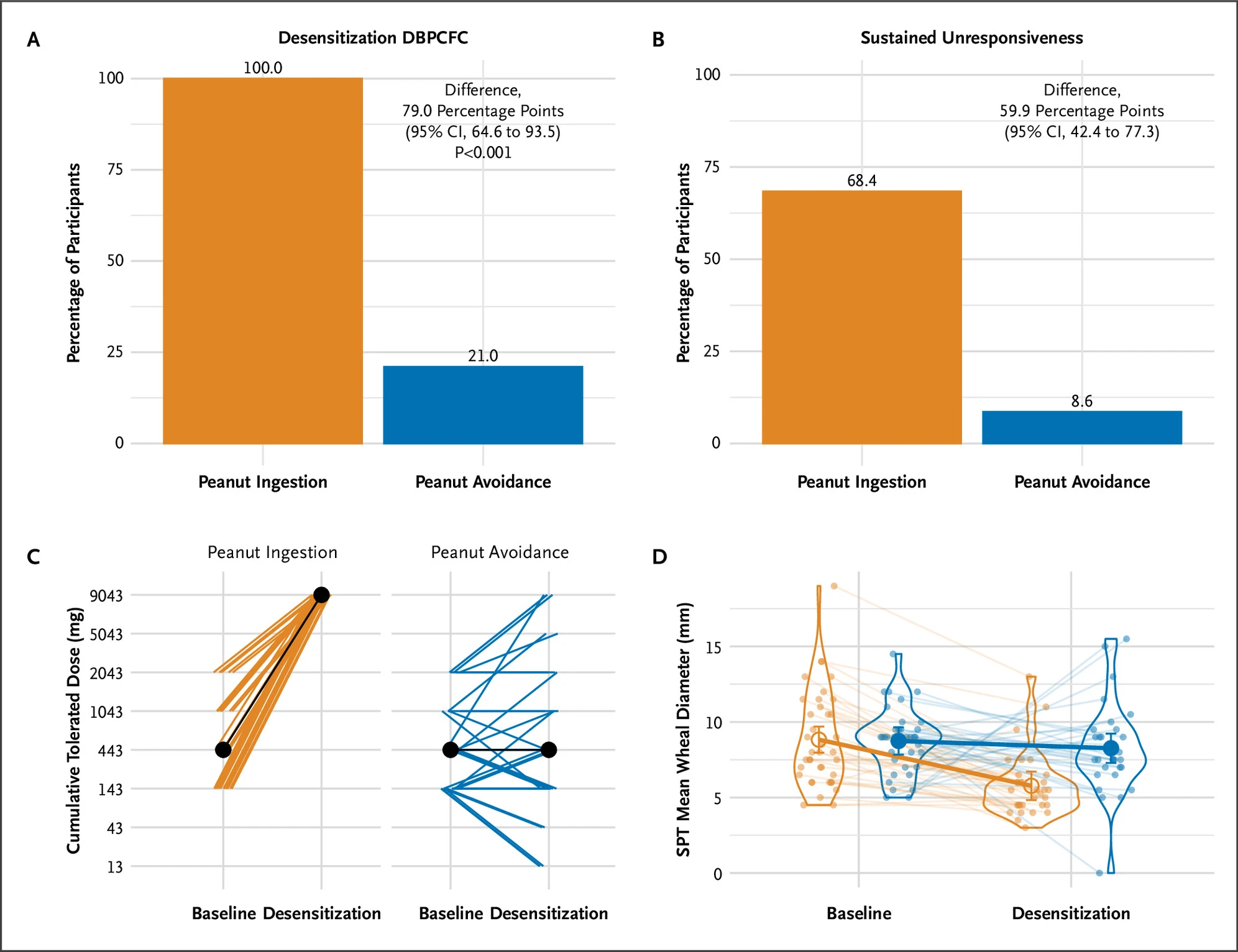

Figure A of this diagram shows the percentage of each respective group that achieved desensitization to peanut product at the end of the trial. Figure B shows the percentage of each respective group that retained that desensitization after being subject to peanut product avoidance. Figure C shows the total dose of peanut product individuals in each respective group was able to tolerate from baseline to the end of the trial. Figure D shows the size of wheals of participants in each group when subject to a skin prick test, from baseline to the end of the trial.

After 18 months, both groups were tested on how much peanut they could eat without an allergic reaction. Among those who completed the study, all 32 children in the ingestion group could tolerate two and a half tablespoons of peanut butter. Only 3 of 30 children in the avoidance group could tolerate that amount.

Jackson, who was in the ingestion group, had no issues with the escalation doses. He is currently working with Dr. Sicherer to address his other allergies.

“Today, Jackson is safely eating peanut butter. Not only were we able to open up his diet, but we forged a bond with the Mount Sinai community who deeply understand the need for innovation, treatment, and prevention of food allergy disease,” says Ms. Esteves.

“I am incredibly grateful for our trial experience, for the wonderful professionals who took care of us, and for the research that I hope will help thousands, if not millions, of people,” she says.

And the CAFETERIA study didn’t offer just Jackson a new lease on life—it took a weight off Ms. Esteves too. “I used to lead conversations with an apology for being a bother about Jackson’s allergies, but not anymore. Now I lead with compassionate command,” she says.

A Mother’s Resolve: Navigating your child’s food allergies can be challenging—and highly fraught. In this episode of the Road to Resilience podcast, Holly Esteves describes how faith, diligence, and lots of medical advice helps her keep her son Jackson safe despite severe allergies to foods, including peanuts and dairy. Click here to listen.

What It Takes to Get to the Next Stage

Scott Sicherer, MD, left, with Hugh Sampson, MD, Kurt Hirschhorn, M.D./The Children’s Center Foundation Chair in Pediatrics, whose lab focuses on the humoral immune system and the proteins it makes that cause allergic reactions.

With the CAFETERIA study concluded, Dr. Sicherer and his team are already contemplating next steps. The biggest question: Can this method of immunotherapy be replicated in other food allergies?

A clear, direct way to test that would be a formal multicenter study in different types of food, says Dr. Sicherer. “That would be a huge undertaking—a clinical trial like that would require, perhaps, in the ballpark of $15 million, and years to run.”

But should the team’s hypothesis prove right, it could change how allergists can treat and advise children with high-threshold food allergies.

“A decade ago, allergists used to tell patients to completely avoid a food they were allergic to, even if they had a threshold before getting a reaction,” says Dr. Sicherer. “With the findings from the CAFETERIA study, it could be a future where patients could work with their doctors to start small, and eventually overcome their allergy.”

Specialists in the field have indicated interest in this new possibility, notes Dr. Sicherer. In a survey his team did, many allergists said they were open to recommending that patients with high-threshold allergies attempt a food escalation challenge.

Basic Science Matters Too

Supinda Bunyavanich, MD, MPH, MPhil, Mount Sinai Professor in Allergy and Systems Biology, has a lab focused on studying systems biology in allergy and asthma.

Even as the team is applying for grants from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) to fund that trial, researchers at Mount Sinai are working on parallel questions that the CAFETERIA study couldn’t address.

“Pharmaceutical companies have long focused on developing options for people who have low-threshold food allergies—meaning they react even to the slightest amount,” says Dr. Sicherer. “But not all patients with allergies are the same. What if they have higher thresholds, then how do we know which strategy—be it our protocol from the CAFETERIA study, or the commercial drugs—is best suited for them?”

There are two Food and Drug Administration-approved treatments for food allergies: Palforzia, peanut allergen powder, used as ingested immunotherapy for children with confirmed peanut allergies, and Xolair® (omalizumab), an injected antibody therapy used to reduce the risk of allergic reactions in case of an accidental exposure.

“Furthermore, we need a better way of identifying allergy thresholds in patients other than by feeding patients increasing amounts of a food to see when symptoms start,” says Dr. Sicherer.

A key to answering those questions: biomarkers. Researchers at the Elliot and Roslyn Jaffe Food Allergy Institute and elsewhere in the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai are tackling biomarkers at all levels, from basic science to human models. Some ongoing allergy research at labs at Mount Sinai include:

Hugh Sampson, MD, Kurt Hirschhorn, M.D./The Children’s Center Foundation Chair in Pediatrics, focusing on the humoral immune system and the proteins it makes that cause allergic reactions.

Maria Curotto de Lafaille, PhD, working on B cells and food allergies.

Erik Wambre, PhD, Director of Technology and Business Development at the Human Immune Monitoring Center at Mount Sinai, working on T cell responses in food allergies.

Supinda Bunyavanich, MD, MPH, MPhil, Mount Sinai Professor in Allergy and Systems Biology, studying systems biology in allergy and asthma, including the microbiome.

These teams are firing on all cylinders to gather support. “Even philanthropic support can lead to something greater,” says Dr. Sicherer. “After all, that’s how the CAFETERIA study got started.”

To get NIH funding, one needs preliminary data as part of the application. In 2015, the Elliot and Roslyn Jaffe Food Allergy Institute launched the Food Allergy Treatment and Research Center, which is supported by philanthropy. The research center had a high success rate with a pilot study that was the precursor of the CAFETERIA study. With those findings, Dr. Sicherer applied for NIH funding in 2017, and was awarded the grant in 2018.

In a way, the journey of this research has similarities with the treatment protocol, where patients escalate from one dose to the next, eventually getting their desired outcome, notes Dr. Sicherer.

“In this case, it began with small philanthropic support, leading to a small study and idea, which then led to the CAFETERIA study,” he says. “I can’t wait to see where it goes next.”

—By Shuan Sim

Click here to read another inspiring story about research that saves lives at Mount Sinai