One of the world’s top neuroscientists, Eric J. Nestler, MD, PhD, was named Anne and Joel Ehrenkranz Dean of the Icahn School of Medicine in October 2025. Four months earlier, Dr. Nestler had been named Interim Dean of the Icahn School of Medicine and Executive Vice President of Mount Sinai Health System.

Known for research that has revolutionized understanding of the molecular basis of drug addiction and depression, Dr. Nestler joined Mount Sinai in 2008 as the inaugural Director of The Friedman Brain Institute. In 2016, he was appointed Dean for Academic and Scientific Affairs of the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, and in 2021 he was named Chief Scientific Officer for the Mount Sinai Health System.

In an interview conducted during the months he was Interim Dean, and revisited after his appointment as Dean, Dr. Nestler talked about his vision for the Icahn School of Medicine, his discoveries in the lab, and how his distinguished career has prepared him for this next challenge.

One of your many positions at Mount Sinai has been Dean for Academic Affairs. So, becoming Dean of the School of Medicine is not exactly new territory for you.

That’s correct. I took on the role of Dean for Academic and Scientific Affairs in 2016, so it’s been almost nine years, and I learned a lot in those years. I do think it was great preparation for becoming Dean.

How has your career in science and medicine prepared you to lead the Icahn School of Medicine?

Over the last 38 years that I’ve had a lab, I’ve learned a lot about research, research administration, research funding—everything involved in doing, managing, and supervising research.

In 2000, when I became Chair of Psychiatry at The University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center at Dallas, I expanded my knowledge to the clinical world. I’m a trained doctor, a psychiatrist. So patient care was something I knew well. But in terms of managing doctors, managing patient care, clinical units, it was a whole other world of administration, which also provided essential preparation for me to serve as Dean.

Education is the third piece, and that is something all of us in academic medicine have spent quite a bit of time in—for me both medical school and graduate school education. I, therefore, feel very well prepared to provide leadership in that domain, as well.

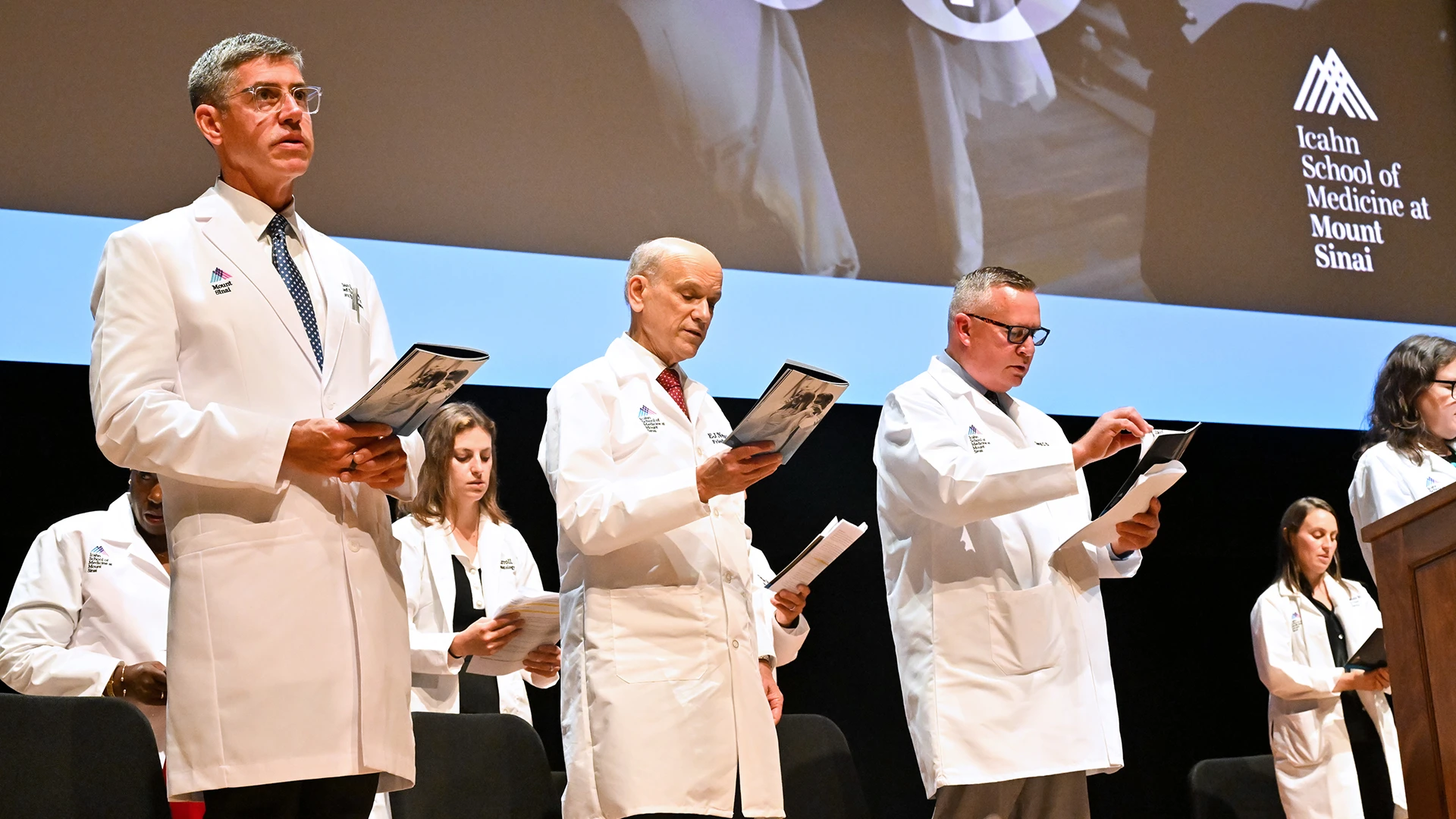

Eric J. Nestler, MD, PhD, center, was joined at the 2025 White Coat Ceremony by Brendan G. Carr, MD, MA, MS, left, Chief Executive Officer and Professor and Kenneth L. Davis, MD, Distinguished Chair, Mount Sinai Health System, and David C. Thomas, MD, MHPE, Dean for Medical Education. "Medical practice today is far too much the same as it was when I was in medical school 40 years ago, and far too much the same as my mentors experienced 40 years before that," Dr. Nestler told the medical students. "Like the space explorers of the 1960s, who overcame setback after setback to eventually land on the moon, our mission to uncover the deepest secrets of human biology has gradually surmounted countless challenges to bring new advances to clinical practice. ... Now, with the aid of artificial intelligence, the spaceship of biomedical exploration is about to accelerate at warp speed."

What is your vision for the School?

Mount Sinai is one of the United States’ elite biomedical and health care institutions. My goal, my expectation, and my commitment are to not only maintain Mount Sinai's recognition as an elite institution, but also to bring it to even greater heights and continue our quest for excellence.

What is the difference between the Icahn School of Medicine and the other medical schools in the United States?

The fact that we’re not part of a larger university gives us more latitude and flexibility, allowing us to be nimble and agile, more adaptive, and able to innovate in a quicker and more effective manner.

Can you give us an example?

When I was a sophomore at Yale, a professor told me that neuroscience was a new field, and Yale was going to create a Department of Neuroscience. It was 1974. Yale created its Department of Neuroscience somewhere around 1997. It took more than two decades for one of the world’s great research universities to create a Department of Neuroscience because of the bureaucratic and administrative obstacles it faced. Here at Mount Sinai, Dennis Charney approached me in 2007 and said he wanted to start a brain institute. We did it the next year. Two years after I started, Trustee Rich Friedman stepped up to fund The Friedman Brain Institute and got us on our way. Another Trustee, Joshua Nash, and his family also provided essential support for us. So, from conception of a brain institute to having a named institute that was off to the races—competing with the best places in the country—took us just a few years.

In terms of research progress, how did Mount Sinai’s willingness to take a chance and place big bets make a difference?

One of the things we’ve been able to do at The Friedman Brain Institute is to achieve what I call a functional integration across all the fields of neuroscience. When I was in medical school, many of us felt there should be just one clinical neuroscience discipline, so when a person has a brain disorder, every specialty is brought to bear. But because neurologists and psychiatrists have different perspectives and unique professional cultures, that hasn’t happened, nor will it happen any time soon. Nevertheless, here at Mount Sinai we’ve been able to bring neurology, psychiatry, neurosurgery, rehabilitation medicine, ophthalmology, and many other departments together as one unit, including, importantly, a basic neuroscience department as well. We now have clinical units where neurologists, psychiatrists, neurosurgeons, and psychologists are all there to take care of patients in an integrative manner. I think we do that better than any other place in the country.

You led The Friedman Brain Institute for many years. What are some of your team’s standout achievements that give you hope that we're going to conquer highly complex brain diseases?

We have made tremendous advances in identifying genes that predispose people to the broad range of neurological and psychiatric diseases, from autism to Alzheimer’s disease to depression and everything beyond that. We have made critical advances in understanding the biology of what goes wrong in that spectrum of diseases. In many cases, we have developed novel treatments, some of which have already been approved by the Food and Drug Administration, and many, many more in earlier stages of development about which we’re enthusiastic. For example, we have a new treatment for one type of autism, new treatments for depression, new treatments for schizophrenia, and advances in diagnosing all of those illnesses as well.

How are the researchers, educators, and clinicians at Mount Sinai driving the future of science and medicine?

I want Mount Sinai to continue being a place where outstanding, talented people—across education, research, and clinical care—are able to innovate, to think as boldly as possible. No idea is too big or bold for us to consider. Something like two-thirds of adults have at least one chronic disease, and more than a third have multiple chronic diseases. The only reason a disease is chronic is because there isn’t a treatment for it or a way to prevent it in the first place. That’s where we really need to focus: on healthy living and how to maintain health throughout the lifespan—from before birth all the way through advanced old age—to help people reach their potential from a healthy living point of view.

In Nature: Mount Sinai Ranks No. 5 Among Leading Research Hospitals

Nature recently published a global ranking of leading research hospitals based on research output over a five-year span ending in 2024, and the Mount Sinai Health System was ranked No. 5. Together with the Index, Mount Sinai sponsored an article about its approach to being a research hospital, introducing the concept of Mount Sinai as a learning health system. Click here to read the article.

Speaking of advances, can you tell us a bit about your research into the molecular mechanisms of drug addiction and depression?

I earned my PhD in basic neuroscience. I had the tremendous opportunity of having Paul Greengard, a Nobel Prize-winning researcher, as my mentor at Yale University. When I finished my psychiatry residency and opened my own lab, I wanted to bridge my two worlds, basic neuroscience and psychiatry. I chose to focus on drug addiction because I felt that animal models of drug addiction were much more straightforward than animal models of other psychiatric syndromes.

Over the last four decades, we’ve learned a tremendous amount about drug addiction. We now know where in the brain the drugs act to produce these changes. We’ve learned a lot about the ways in which the drugs change the chemistry of individual cells in those regions and can draw causal connections across molecular, cellular, circuit, and behavioral adaptation. For example, cocaine causes a particular change to a type of nerve cell, and the chemistry of that cell changes as a result, and that makes that nerve cell behave differently in a larger circuit, causing an addiction behavior. We’ve established that type of causality, and now the next goal is to mine the information to develop better treatments.

You’ve also discovered proteins that mediate response to chronic stress. How is that influencing the potential for new treatments?

Most of what happens in response to stress is adaptive, helping the animal cope with stress. We were able to develop assays to identify the changes that are pro-resilient versus the other changes that are pro-susceptible. We guided the field to focus not only on undoing the bad effects of stress, undoing the pro-susceptible changes, but to also mimic the pro-resilient changes. That has been quite successful, and we now have several examples of resilience-boosting new treatments that are in various phases of clinical development to treat depression.

You were recently honored with election to the National Institute of Sciences, and you’ve long been a member of the National Academy of Medicine. What were your thoughts upon receiving the latest honor?

It’s always a tremendous honor to be recognized by one’s colleagues. It’s the dream of a lifetime. I remember when my PhD mentor was elected to the National Academy of Sciences. That was when I was working in his lab, long before he won the Nobel Prize. And I remember seeing how excited he was to have been elected. It was very meaningful for me to receive that same recognition.

How do you plan to leverage advances in genomics and artificial intelligence to make patient care more personalized and effective?

Mount Sinai has made robust investments in genomics and AI. Our Mount Sinai Million Health Discoveries Program, through which we will obtain the genome sequences of a million Mount Sinai patients, is unprecedented in the world. And Mount Sinai was the first U.S. medical school to establish a Department of Artificial Intelligence and Human Health. We all know there will be a day relatively soon—perhaps in 5 to 10 years—when every patient seen by a doctor will have their genome sequenced. The bioinformatic analysis of that sequence will be combined with the patient’s entire electronic health record (including all imaging, blood work, EKGs, and the like) and with all digital data (obtained from the patient’s wearable devices) to derive novel insight into risk for diseases, diagnosis of a current illness, choice of treatment, and eventually disease prevention. AI and machine learning will be instrumental for that synthesis, with the patient’s genome being the foundation of the analysis. This is the future of medicine—a truly revolutionary advance in the way we conquer disease and promote heath—and Mount Sinai will be at the forefront nationally and internationally in making this future a reality.